How does a Ukrainian live, who testified against Sentsov and received a pardon from Putin?

A few years ago, a resident of Simferopol, Gena Afanasyev, was an apolitical photographer with a law degree and experience in the United States. Today he, to put it mildly, is a controversial figure. Some are amazed at his perseverance and strength of mind, manifested in more than two years in Russian prisons. About this in a report for BBC Russia writes journalist Svyatoslav Khomenko.

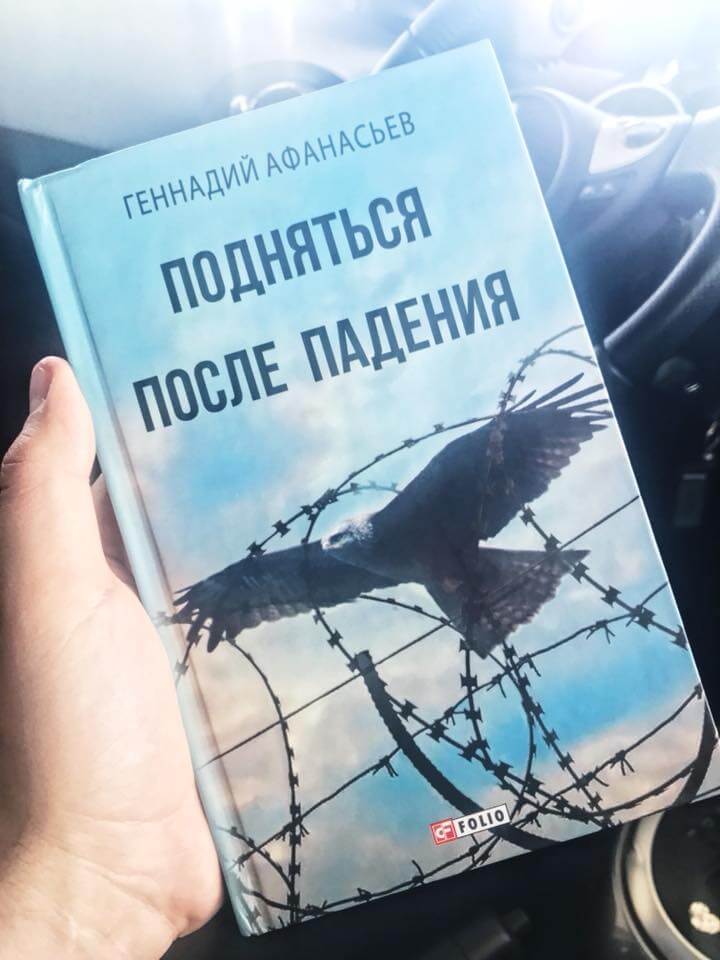

Photo: Facebook Gennady Afanasyev

Others accuse him of almost all mortal sins: they insist that it was because of him that Oleg Sentsov ended up behind bars, they reproach him for not disdaining to ask Vladimir Putin for clemency, and they denounce him, saying that all his activities are in defense of Ukrainians convicted in Russia - this is window dressing and PR.

Gennady Afanasyev answers his critics: they do not care about their accusations, and certainly not for them to judge him for what he did or what he did not do.

When I meet Gennady Afanasyev, a short guy with an intricate tattoo all over his arm, I can’t help but remark: “We can make films based on your story.”

He smiles shyly and replies: “No, thank you. I wrote a book, that’s enough for now.”

Afanasyev is a defendant in the case of a “terrorist community,” which, according to investigators, was created by Ukrainian director Oleg Sentsov. Members of the community, as the Russian court decided, planned to carry out a series of explosions in Simferopol. At first, Afanasyev cooperated with the investigation, but later refused to testify - he says that he gave it under torture.

Sentenced to seven years in prison, he was nevertheless pardoned by the President of Russia, and after his release he received the post of special representative of the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry on the release of prisoners, held countless meetings in support of Ukrainians convicted in Russia and described his story in the book “Rise After falls."

Photo: Facebook Gennady Afanasyev

Today, social activity is gradually fading into the background for Gennady Afanasyev, he tells Bi-bi-si.

In “peaceful life” he retrained as an “IT specialist”, works in one of the Kyiv computer companies, strives to overcome his traumatic experience and dreams of quickly hugging Oleg Sentsov, now serving a 20-year sentence in a Russian prison.

I talked with Gennady Afanasyev about the details of Sentsov’s case, about clemency from Putin’s hands and about life after a Russian prison.

“It was not terrorism. We were engaged in sabotage"

Begin 2014 of the year. Gennady Afanasyev 23, he lives in Simferopol, earns mostly with photography, and at the same time works in his mom's travel agency.

“In absolutely no way did I interfere with politics. It’s just not,” he laughs.

Everything changed in February, when Afanasyev drove from Kiev to the homeland of the Carpathians to his native Crimea, where Euromaidan protests continued at that time. Communicating with the participants, Afanasyev recalls, convinced him: it is not just about regular meetings, but about the struggle for fundamental changes in the country, which he could not stay away from.

Afanasyev left Kiev several days before the shooting of protesters in the center of the Ukrainian capital. In Crimea, he joined local protests against President Viktor Yanukovych.

Then, at the end of February 2014, in the center of Simferopol, mass actions of Crimean Tatars, Euromaid supporters and pro-Russian activists took place simultaneously. However, the situation radically changed on the night of February 27, when unknown armed people in uniform without insignia seized the building of the Supreme Council of Crimea and raised the Russian flag over it.

It was then, says Afanasyev, he, together with his comrades, whom he met at previous rallies, decided to act.

“We reasoned like this: there are people with weapons around, we can’t do much against them, so we’ll help our people. We thought that either some kind of Maidan would begin in Crimea, or that the Ukrainian military would begin to resist Russian aggression. We decided that in this situation we could provide medical assistance to the participants in these events. This is how our first aid courses were born,” he recalls.

Activists agreed to cooperate with professional doctors, found premises for these classes, purchased medicines and T-shirts with helmets for future volunteer doctors. At the same time, Afanasyev says, they helped journalists who came to Crimea to cover events on the peninsula, supported the Ukrainian military in military units that were then blocked by Crimean “self-defense” activists and “little green men.”

As it turns out later, these “little men” were career soldiers of the Russian army.

“From thirty people, we quickly grew to about two thousand - but that’s all who could be raised through all our acquaintances and gathered for some kind of action. There were about a hundred active participants,” says Afanasiev.

Did Oleg Sentsov belong to this circle? Afanasyev admits: perhaps he met him in those days.

“Here you need to understand: when I talked to people, I didn’t look at their documents. Well, what will a 40-year-old director do with a 23-year-old guy? It's hard to imagine us hanging out together somewhere. Maybe we crossed paths somewhere and saw each other. But this is not something that is remembered,” he says.

16 March The 2014 of the Year in Crimea held a referendum on the accession of the peninsula to Russia, which was not recognized by the international community. Pro-Ukrainian activists began to travel en masse from the Crimea, Afanasyev recalls, while he himself coordinated the work of like-minded people in Simferopol.

“I was sitting on the phone like a director in some company: let’s buy a spray can and go draw “Glory to Ukraine!” on the fence at night, are you a patriot or not a patriot?” he laughs.

Activists painted the walls and fences with pro-Ukrainian and anti-Putin slogans, threw agitation boards with condoms with paint, pasted flyers, he recalls.

“What we were doing was not terrorism at all. We were engaged in sabotage,” says Afanasyev, smiling.

And he already seriously claims that he was not involved in the arson of the offices of United Russia and the Russian Community of Crimea in April 2014, which the FSB would later impute to the “Sentsov group” with Afanasyev in its composition.

“The lawyer said: it’s okay, they beat everyone, it’s normal, you admit it”

It cannot be said that Afanasyev did not feel the attention of Russian security forces. He says that his mother received calls at work from employees of the “Security Service of Crimea,” which arose after the annexation of the peninsula instead of the Security Service of Ukraine.

“They threatened my mother that I would have problems, she cried. In another call, she called me for an “interview.” I told my mother that I wouldn’t go anywhere without a summons,” the activist recalls.

“Of course, I kept in mind that [I] could be detained and beaten, but I couldn’t even think about arrests and torture,” continues Afanasiev.

9 May 2014, FSB operatives detained Gennady Afanasyev right on the parade in honor of Victory Day.

“They put me in the back seat of the car between two people. They hit me in the stomach and asked some questions to which I did not know the answers. Who is Chirniy? Where did you meet? Some other names. Some mines at Belbek airport,” recalls Afanasyev.

They brought him from the parade to his apartment and searched it. Then he went to the FSB building, where he was accused of planning to plant a bomb near the Simferopol Eternal Flame.

“They also talked about some bombs - it was some kind of enchanting nonsense. They frightened me: “Come on, admit it, it will be easier,” says Afanasiev. “They took me to another room, and these guys who detained me began to beat me. They beat, beat, beat... Then a lawyer appointed by the state came. He asks: were you beaten? And the FSB officers were standing outside the door, I nodded to him: they beat me. He says: nothing, everyone is beaten, this is normal, you admit it.”

The next ten days Afanasyev spent in the temporary detention center.

“Every day in the morning they came for me, let me get dressed, threw me into the trunk and took me to the FSB. Same questions, same threats,” he says.

On one of these days, Alexey was brought to Afanasyev, a man who from time to time came to the first aid courses he organized. It turned out that this was Chirniy, about whom he was questioned during his arrest.

“He came in and started: I am so-and-so, with this [Afanasyev] we wanted to blow up, kill, cut, disembowel. And then, right in front of the FSB officers, he said: “Sorry, that’s what happened,” recalls Afanasyev.

FSB operatives were detained by Aleksey Chirniy a few hours before Afanasyev. According to the investigation version, in April 2014 of the year he asked his familiar chemical student Alexander Pirogov to make explosives for him. Pirogov appealed to the FSB and later acted under the control of the Russian special services.

The Sentsov case file contains a recording of Chirniy's conversation with Pirogov, taken on a hidden camera. The device was fixed on the body of Pirogov. In the course of this conversation, the interlocutors discuss the explosions that Chirniy allegedly intends to carry out.

“I want Muscovites to feel horror,” Mediazona quotes the words spoken by Chirniy in this recording.

Although the names of Sentsov and Afanasyev are not mentioned in the mentioned recording, Chirniy names them in his written testimony, which he gave after the arrest. In them, the man claims that the group he was part of was created by Sentsov, and it was he - at times through Afanasyev - who gave orders to it.

In April, 2015, Alexei Chirniy was sentenced to seven years in prison, and today his name appears on the list of Ukrainians, whose release Kiev is seeking from official Kiev.

“After [the meeting with Chirniy], they took me into another room, put a gas mask on my head, and began to choke me. And when I was choking, they injected some kind of gas into me, I began to vomit, and I choked on my vomit. I don’t know how to explain this,” recalls Afanasyev.

According to him, then he signed a statement about his intention to carry out explosions in Simferopol.

“They said that this would all end. But nothing ever ends there for them,” he says after a pause. “At night they came to my temporary holding cell with new papers, where Kolchenko and Sentsov were already there. That's all. They started shocking my genitals. They threatened with rape,” recalls Afanasyev.

So, he says, his signature appeared under written testimony, in which Oleg Sentsov is called the organizer of the terrorist community.

“In prison I had more or less authority”

Gennady Afanasyev’s cooperation with the investigation allowed him to receive a relatively lenient sentence under the “terrorist” article: in December 2014, he was sentenced to seven years in prison.

He spent more than a year in the Moscow Lefortovo pre-trial detention center, and in July 2015 he was taken to Rostov-on-Don, where the trial of Oleg Sentsov and Alexander Kolchenko took place. There he was supposed to act as a witness: it was expected that he, like Alexey Chirniy earlier, would simply confirm the confession given during the pre-trial investigation.

However, on July 31, Afanasyev unexpectedly announced that all his previous testimony had been given under duress, and later, through his lawyer, he spoke about the torture that was used against him. Oleg Sentsov greeted Afanasyev’s statement with applause and the cry of “Glory to Ukraine!”

“In fact, I regret that I did not do this at my own trial, but then I was in a rather difficult psychological state. No one wrote to me then, no one helped my family. At some point I decided: if I couldn’t live as a person, then at least I would die as a person, and I decided to wait for some opportune moment. And so I waited,” Afanasyev explains the motives for his action.

After refusing to testify, he was transferred to the Komi Republic in an experimental colony with harsh conditions of detention.

But, Afanasiev admits, he was very lucky there. Shortly before he was taken “to the zone,” a certain Crimean, a crime boss from the 1990s, called “the barracks” and asked to “properly receive” his fellow countryman.

“I don’t know why he did this, I’ve never seen him in person. Probably only because I am a Crimean. Perhaps because he was also a patriot of Ukraine. But this call helped me a lot. As soon as I entered the colony, people met me and said: they called us for you, come in, everything will be fine with you,” he says.

Afanasyev remembers about prison life without unnecessary emotions: he learned to communicate, he turned on his comrades. Being a lawyer by training, he helped other inmates to write complaints and appeals.

“I had more or less authority: I learned how to make prison maps and was the only one in a barracks of a hundred people who knew how to make them - and this is quite an honorable job in prison,” he smiles.

In addition, Afanasyev recalls, he fought against the system: he wrote several letters every day to the most diverse Russian state bodies about the violation of his rights.

“It’s stupid to refuse when they say: let us free you”

At some point, says Gennady Afanasyev, a SIM card was planted on him, which became the basis for his transfer to a “single cell-type room” - a place with even more harsh detention conditions. There, the prisoner's health seriously deteriorated: purulent ulcers appeared all over his body, which caused him severe pain.

“I cut them out with a sharpener, using Alice baby cream as an antiseptic, and torn sheets as bandages,” he recalls. Afanasyev admits that he was thinking about imminent death.

Therefore, when, one morning, he was transported back to the colony without any explanations and offered to write a petition for clemency, he simply did not believe it.

“I’m a “seasoned prisoner”: yeah, I say, here every day everyone is pardoned and released. I have never seen a single person in my life who was released from prison through a pardon,” he recalls.

But soon Afanasyev and his lawyer came to the rumors that Russia is seriously discussing with Ukraine the possible exchange of prisoners.

“My lawyer came to me and said: let’s try. If you are not released, yes, it will be bad, but you still do not lose anything, but if you are released, then we will see that in this way we can negotiate with Russia on the release of our people. And I thought: why not?,” he explains.

Shortly before that, Russia issued a pilot to Ukraine, Nadezhda Savchenko, accused of the murder of two Russian journalists during the fighting in the Donbas.

Savchenko stated that she would not ask for pardon from Vladimir Putin and, in the end, the petitions of the bereaved Russian journalists became the formal basis for her release.

Afanasyev says that for him, the request for pardon was just a formality: “This is simply a form of Russia legitimizing my release.”

“It’s stupid to refuse when they come to you and say: let us free you,” he says.

On May 30, 2016, Gennady Afanasyev and 74-year-old Ukrainian citizen Yuri Soloshenko, previously convicted in Russia of espionage, signed pardon petitions addressed to Vladimir Putin. Two weeks later they returned to Ukraine. In exchange, Kyiv extradited to Russia two activists of the “Bessarabian People’s Council”, who were accused of separatism.

Why did the Russian authorities offer pardon to Afanasyev and Soloshenko?

“[We] just got overwhelmed because of our health condition.” They were afraid that Soloshenko would die there, and my state of health was such that they did not rule out my death,” Afanasiev suggests.

Yuriy Soloshenko was sick with cancer. He died in April 2018.

The second factor, Afanasiev continues, was his “fight against the system.”

“I really bored them with my daily complaints, which I sent several times a day to all possible authorities,” he says.

Gennady Afanasyev calls the hunger strike, announced by Oleg Sentsov on May 14, another form of struggle against the system.

He admits that fulfilling Sentsov’s demand—the release of 64 Ukrainians convicted in Russia for political reasons—looks unrealistic, and the real purpose of the director’s hunger strike may be to encourage the Ukrainian authorities and Ukrainian society to more actively seek the exchange of prisoners, to draw attention to this topic.

“There is no such hype [around the topic of political prisoners] as there was around Nadezhda Savchenko,” sighs Afanasiev.

“I would just like to hug Sentsov and Kolchenko”

Adapting to life in freedom after returning to Kiev did not go easily, says Gennady Afanasyev.

“This is just tough. At first you don't understand it. There are journalists, politicians, the international community around you - go and tell all the things that I am telling you now. But it’s difficult to talk about it, and only after about a year do you realize what trash it is,” he says emotionally.

“A person needs to return to life, communicate with psychologists, and move on with life. But they don’t let you live, they force you to revolve around this again and again, even if you don’t want to go anywhere or participate in anything,” he continues.

In the first interviews after his release, Gennady Afanasyev admitted that he would engage in political activities. He does not leave these thoughts now.

Photo: Facebook Gennady Afanasyev

“I don’t want it, but I don’t rule it out. On the one hand, this is an interesting experience, this is a chance to do something. On the other hand, the Ukrainians themselves discouraged me from going into politics,” he explains.

“I gave a lot of energy and health to travel around the world, talk about the situation in Crimea, engage in diplomacy, help political prisoners and their families, and what did I get as a result? Accusations on social networks, from human rights activists and media parties: you handed over Sentsov, you asked Putin for a pardon, you are promoting yourself, you want to go into politics,” says Afanasiev.

“Sometimes I want to tell these critics: go to Crimea, organize some kind of resistance there. Go to prison in Russia and decide whether to sign a pardon petition or not,” he continues emotionally.

Today, Gennady Afanasyev is unable to maintain contact with Oleg Sentsov: his name appears on the “terrorist list” of Rosfinmonitoring, so his letters do not reach the colony.

When asked what he would say to Sentsov and Kolchenko after their possible release, Afanasiev replies: “I would like to just hug them. Whatever I could say or do for them, I did.”

Read also on ForumDaily:

The “testament” of Sentsov to the sounds of the sea touched the social network. VIDEO

The New York Times supported the Ukrainian Sentsov, who is being held in a Russian prison

Mother of a Russian convict in Ukraine asked Trump for help

Between the USSR and the USA: why I decided to write a spy novel about the Cold War

Subscribe to ForumDaily on Google NewsDo you want more important and interesting news about life in the USA and immigration to America? — support us donate! Also subscribe to our page Facebook. Select the “Priority in display” option and read us first. Also, don't forget to subscribe to our РєР ° РЅР ° Р »РІ Telegram and Instagram- there is a lot of interesting things there. And join thousands of readers ForumDaily New York — there you will find a lot of interesting and positive information about life in the metropolis.