Sociologist about how Russian-speakers are changing in America

Sociologist Sam Kliger has been observing, studying and describing the Russian-speaking community of America for three decades. In Soviet times, he worked in Moscow at the Institute of Sociology of the Academy of Sciences, in 1990, after ten years of refusal to leave, he fled to the USA and came to New York.

In immigration, Sam created the research institute RINA (Research Institute for New Americans) and runs it to this day. He also taught and counseled immigrants at Nayana, the New York Association for New Americans. Now he is also the director of the Russian Department of the American Jewish Committee.

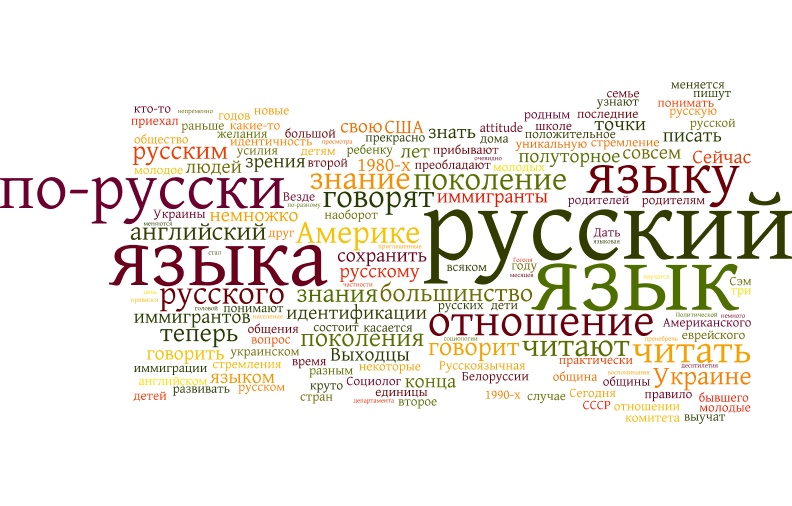

The “Forum” talked with Sam Kliger to understand what the Russian-speaking community in the US breathes, whether its appearance is changing, and how it now speaks. It turns out that new immigrants completely differently refer to the language and use it both for integration and for identification.

How has the attitude towards the Russian language changed in the Russian-speaking community over the past three decades?

To answer this question, it is necessary to outline the boundaries of the Russian community and define the concept of “attitude”.

The Russian-speaking community is not at all homogeneous in terms of language problems. It consists of people of different nationalities, but it is still dominated by those who - one way or another - associate themselves with the Jewish community (60%-70%).

If the Jews constituted the overwhelming majority in the immigration flow of the end of 1980-1990-s, in recent years there are few of them among the immigrants, the majority now come from Ukraine and Central Asia. And if 20 years ago, immigrants entered the United States as refugees, now they come here through a variety of channels: refugee, work, school, family reunion.

A more significant factor in attitudes towards the Russian language is not the nationality, but the age of the immigrant.

However, a more significant factor in attitudes towards the Russian language is not the nationality, but the age of the immigrant.

For the most part, immigrants themselves are older people, for them Russian is their mother tongue. Most of them speak and read in Russian, for them, Russian will probably remain until the end of their life native, although, of course, many have a quite strong second language - English.

But in their families are complex and contradictory processes.

For the one and a half generation (who arrived at a relatively young age and grew up in America) and the second generation (born to immigrant parents in America), English became their native language, and Russian, on the contrary, became their second language. This is almost obvious: children go to kindergarten, to school, they are socialized in an English-speaking environment, and English is their first language. At the same time, they also retained Russian thanks to their family - grandparents, parents, television.

The problem is that the one and a half and second generations practically do not read or write Russian. They perfectly understand Russian speech, at least at the everyday level, and speak with varying degrees of success - some better, some worse. But they can no longer read and write. And Russian classics are read in English. The general attitude towards the language on the scale “very positive - positive - neutral - negative - absolutely unacceptable” is rather positive.

Was it always like this?

Not at all. Those who arrived in the 1970s, and perhaps even in the early 1980s, or, in any case, their children, noted a rejection of the Russian language: everything Russian was associated with the Soviet - with the evil empire and the like , at school they were teased as “reds”. Then the attitude towards the language was negative: we don’t need Russian, we will only speak English.

The situation has changed since the big wave of immigration of the end of 1980-x - 1990-x, when the attitude to the Russian language has become much more positive and remains so, although recently with some reservations.

If we take the younger generation - one and a half or two, then, as I already said, unfortunately, many do not read or write, but, on the other hand, being Russian for them is a little cool, cool.

Being Russian for young people today is cool. And others treat them with interest.

Interesting things happen: in the companies they recognize each other by some signs - either by their habits or by the nuances of clothes. The main thing is that they are drawn to each other, which had never happened before. They flaunt Russian words, they can curse ... And the people around them treat them with interest - like those who know some other language, who have some special memories, knowledge, own or received from their parents.

Although there was a period of neutral attitude, when the generation and a half did not shy away from the Russian community, but still strived to completely immerse themselves - to integrate into American society.

If being Russian is cool, then there are more people wanting to learn the language?

Learning a language requires a lot of effort, if by “know” we mean “read”. Now generally a generation is not reading. Reading is work. So the desire to know the language deeply is possible, but only a few are ready to make efforts for it.

Natives of Russian-speaking families in colleges, as a rule, take the course of the Russian language - as an easy way to get extra points (“loans”). And recently there was an opportunity to take Russian as a second language at the final exams at school. But these courses do not give a real knowledge of the language: they do not read serious literature in Russian.

However, in America there are many “Russian schools” - children's educational centers that teach Russian.

Along with music and mathematics, once a week they will learn some words in Russian, learn how to use them correctly, and learn to read a little. But one cannot dream of knowing the language perfectly. There’s a lot of work involved: writing dictations, reading Anna Karenina. Young people, as a rule, have neither the strength, nor the time, nor the desire to do this.

That is, the attitude to the Russian language is changing?

Yes, today we are celebrating some new trends. It is no secret that in the former Soviet republics national languages increasingly dominate. Today, the young generation in Ukraine, knowing the Russian language, prefers to speak, read and write in Ukrainian. They have a dual language environment - from which they arrive in the states.

Last year, I spent several months in Ukraine as an envoy of the American Jewish Committee. It was everywhere, including Lviv and other western cities of the country. Everywhere I turned to people in Russian. And everywhere they understood me perfectly, calmly reacted, but responded in Ukrainian. In television programs in which the presenter speaks Ukrainian, some of the guests speak Russian without any embarrassment or embarrassment. That is, in Ukraine, the Russian language is quite firmly rooted. In Belarus, almost the entire population speaks Russian, there the Belarusian language is much less ingrained than Ukrainian in Ukraine. The same can be said about Kazakhstan, where, with the exception of certain areas, most people speak Russian.

Another thing is the Caucasus, the Baltic States and Central Asia. Young Georgians do not speak Russian at all, and they do not always understand Russian. The same applies to Azerbaijanis, Uzbeks, Moldovans, Lithuanians.

Russian in America is the language of interethnic communication for immigrants from the countries of the former USSR. But this is no longer the full-fledged Russian language, but a somewhat truncated, everyday one.

This category of immigrants uses Russian because Russian here in America is the language of interethnic communication for immigrants from the countries of the former USSR. But this is no longer the full-fledged Russian language, but a somewhat truncated everyday form. So the current trickle of immigration from the countries of the former USSR is not homogeneous, including from the point of view of the native language.

People from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine speak Russian. But given the current political picture, we must understand that the Ukrainian family, who used to speak Russian at home, will now prefer to teach their child the Ukrainian language in order to maintain their Ukrainian identity. Uzbeks speak Uzbek at home.

In fairness it should be noted that the Russian government is making great efforts - trying to teach, develop the Russian language abroad: it creates Russian cultural centers and schools. The political component in relation to these institutions is probably difficult to ignore. But from a cultural point of view, this is very commendable: the language of Tolstoy and Gogol should be known.

Now young parents seek to keep their children Russian. The previous generation, who arrived without knowledge of English, on the contrary, made sure that children became Americans, English was considered a pass to a new society.

Yes, such a trend exists. But it does not come from the desire to give the child a full knowledge of the Russian language, but from the desire to preserve one’s unique identification. And the uniqueness of this identification lies in the fact that “I am a little Russian.”

As my research has shown, in particular, a whole cocktail of identities coexists very comfortably within an immigrant: I am an American, I am an immigrant, I am Russian, I am a Jew. And the bearer of this mixed identification certainly wants to pass on to their children the component that is associated with the Russian language and culture. Thus, the attitude towards language that we have been talking about is not really about literal language, but about the desire to preserve one's unique identity. This is where young parents’ desire to develop their children’s knowledge of the Russian language comes from.

But as far as this aspiration is realizable - a big question. It is quite possible to give a child knowledge of the language sufficient for communication in the family and even for watching Russian films. But no more: without reading deep, serious literature there can be no complete knowledge of the language. And there will be units to read.

Although parents are not alien in their pursuit and healthy practical consideration: the knowledge of an additional language is a competitive advantage, it is quoted on the market.