USSR space satellites launched with a nuclear reactor on board: one of them fell in Canada

In the modern world there are enough weapons that can kill all life on the planet, but new developments like the promising Russian Burevestnik missile still instill fear in ordinary people. Last but not least, this fear can be explained by the presence of a nuclear power source on the Burevestnik. There have already been cases in history when flying nuclear reactors, although for relatively peaceful purposes, got out of control and fell, says Air force.

Photo: Wikipedia /Federal Government of the United States - Operation Morning Light Fact Sheet, DOE/NV1198

The idea of using nuclear energy to fly into space appeared at the very beginning of the space age. It seemed to specialists the only possible option for long flights.

The very first nuclear power sources in space were radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). They use the energy of the natural radioactive decay of isotopes, while reactors use the energy of a controlled chain reaction of fission of the nuclei of heavy chemical elements - most often uranium.

Compared to reactors, RTGs have low power and low efficiency, but the design of such a generator is much simpler and it can supply spacecraft with energy for a long time without requiring maintenance.

RTGs are still used as power sources in the space industry - such a generator, for example, is on the American Curiosity rover. The use of reactors in space, unlike RTGs, was stopped in the late 1980s.

History in brief

Now SNAP-10A is in orbit and will remain in space for the next 4 for thousands of years, during which, according to developers, the radioactivity of the entire system will be reduced to a low level. After 4 of thousands of years, the device will begin to decline, enter the atmosphere, fall apart, and the active zone will burn, minimizing the ingress of radioactive particles into the atmosphere. At least that's how it was conceived.

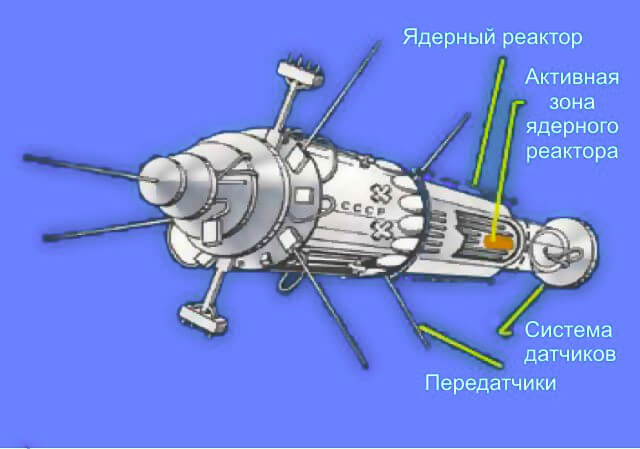

Soviet scientists who developed the BES-5 Buk series of nuclear reactors were counting on approximately the same thing. They were created specifically for the US-A series of satellites (known in the West as RORSAT). The US-A series became part of the Legend naval space reconnaissance system, which tracked American aircraft carriers. A total of 31 spacecraft were launched from BES-5.

"Buki"

The USSR began developing nuclear installations for spacecraft later than the United States. The first prototype - "Romashka" - was successfully tested in 1964-1966, but the installation did not fly into space. The reactor was developed at the Kurchatov Institute.

By the end of the 60s, NPO Krasnaya Zvezda developed a new reactor, the BES-5 Buk, which used uranium-235 as fuel, just like the American one. The first such installation flew into space in October 1970 along with the Cosmos-367 satellite.

The Buk operated for 110 minutes, after which the reactor core began to melt, wrote in their book, space technology testers Vladimir Gudilin and Leonid Slabky. The satellite had to be thrown into the orbit of the burial.

Then three successful launches were carried out. In April 1973, a second accident occurred. This time the launch vehicle failed - due to engine failure, the spacecraft could not be launched into orbit, and the reactor fell into the Pacific Ocean.

After several more launches, a series of US-A radar reconnaissance was adopted in 1975 year.

After this, Soviet testers carried out four successful launches of satellites with nuclear reactors, and on September 18, 1977, Kosmos-954 was launched - perhaps the most famous of the satellites of the US-A system.

What to do when a reactor falls from the sky?

Two months after the launch of Cosmos 954, American radars discovered that it was leaving orbit. писал Advisor to the US Presidential Administration on Technology, Intelligence and Economic Affairs, Gus Weiss.

On 6 on January 1978, American intelligence realized that the Soviet Union had lost control of the satellite. Scientists have determined that it will enter the earth's atmosphere on January 23-24.

Moscow has certainly kept details about its new satellites secret. The United States suspected that Kosmos 954 was using a nuclear reactor as a power source. If this is true, is there a system on the satellite that, in an emergency, will push the reactor into a higher orbit to avoid the nuclear installation falling to Earth?

To get an answer to this and other questions, the United States turned to the USSR directly for information. Moscow in January 1978 confirmed that the satellite contains a uranium-235 reactor, Weiss wrote. Soviet officials ruled out the possibility of a nuclear explosion because the critical mass of uranium at the facility was not exceeded. In addition, the reactor is designed so that it falls apart and burns upon entering the atmosphere, Moscow assured.

At the same time, the Kremlin still did not rule out that, due to the depressurization of the satellite, radioactive debris could reach the surface of the Earth. As a result, minor radioactive contamination of the area may occur, the Soviet Union said in a response.

On the subject: Ukraine and the United States launch a joint nuclear project

“What to do when a Soviet reconnaissance satellite with a nuclear reactor on board enters the earth’s atmosphere?” was how Weiss formulated the problem that faced the world in early 1978.

At the same time, it was not possible to determine the place of fall. The American authorities were thinking whether it would be worth informing the world that a working nuclear reactor, which would soon fall to the surface of the Earth, was slowly descending from orbit. The USSR was silent. The information was about to get into the press and cause a panic.

“What could I do with such a story if I had it a day earlier!” Weiss recalls the disappointment of a journalist friend who learned about the fall of Cosmos 954 after the fact. “You can imagine the headlines,” the adviser wrote.

The United States decided to notify several allies. Specialists, trying to understand where the satellite would fall, calculated possible trajectories, and only one of them passed through the USSR, while several trajectories passed through Canada at once.

“Was he shot down?”

The name for the operation to search for the wreckage of the Soviet satellite - “Morning Light” - was chosen by chance, but it turned out to be somewhat prophetic. Cosmos 954 crashed this morning at 06:53 Eastern Time (EST) in northern Canada.

The book of Goodilin and Slabky states that the reason for the loss of control over the satellite was the failure of the equipment of the autonomous control system.

There were also exotic versions of the crash. For example, the Pravda newspaper reported that Kosmos-954 could have been shot down by an American combat laser, писал Academician and engineer Alexander Zheleznyakov.

On the subject: Security threat: US nuclear weapons and energy depend on uranium supplies from Russia

The newspaper publication said that technical difficulties on the satellite began after it flew over the Woomera test site in Australia. “Supposedly, an American combat laser was installed there and fired at Cosmos-954,” Zheleznyakov recounted the Pravda article.

Conspiracy theological versions were also discussed in the American press. How nisal New Scientist magazine theorized that the Soviet Union could have used an interceptor satellite to shoot down and destroy Kosmos 954, denying its opponents the opportunity to explore the fallen object.

Operation "Morning Light"

On a January morning in 1978, the Soviet satellite Kosmos 954 burned up in the atmosphere, scattering radioactive fuel and debris over an area of 100 thousand kilometers. says in the incident report prepared for the US Department of Energy in September 1978.

Eyewitness accounts have been preserved - residents of the city of Yellowknife, the administrative center of the Northwest Territories of Canada. Several people saw an object that looked like a burning plane with a flaming fiery tail fly through the sky, as well as dozens of small objects that flew behind them, burning and glowing bright red.

Photo: Wikidedia /US Federal Government / NNSA US DOE /

The Buk contained more than 45 kg of uranium. Scientists were worried that the area would be contaminated, among other things, with spent nuclear fuel products - strontium-90 and cesium-137.

Fortunately, radioactive debris fell on an uninhabited territory in the High North. On the other hand, the authorities now had to organize a complex expedition to find debris in the cold snowy desert.

A team of two dozen men was immediately sent to the crash site from the Canadian Forces base in Edmonton (Alberta).

The USA offered their help. Canada agreed. In the United States, five C-141 military transport aircraft with equipment and people were prepared for departure.

Some military and civilian specialists first arrived in Yellowknife. Residents of a quiet northern city were shocked to see people in yellow protective suits walking and measuring radiation, recalled Canadian Forces Major Bill Eyckman.

Specialists identified the territory that had to be examined in search of debris. It turned out about 40 thousand square kilometers between the Great Slave Lake and the Eskimo settlement Baker Lake (later it will become known that the wreckage scattered over an area of 100 thousand square kilometers).

Photo: Wikidedia /US Federal Government/

The terrain was first inspected from aircraft on which there was equipment for radiation monitoring. If an excess of background was noticed in a certain square, then it was examined in more detail from helicopters. The equipment worked around the clock, only the search engine teams changed.

The first wreckage of the satellite was not discovered by the military, but by tourists who set up a winter camp on a river somewhere in the middle between Yellowknife and Baker Lake.

Two of them - John Mordhort and Mike Mobley - were riding a dog sled and saw a twisted metal object that looked like deer antlers. One of the tourists came up and touched the piece of iron. The men returned to camp. Their comrades already knew about the fall of the satellite, as they asked on the radio why planes fly so often. They immediately reported the discovery to the Yellowknife weather station.

The search party was thinking about how to approach the wreckage. If it was an active zone, it could emit several hundred roentgens per hour (the lethal dose is about 600 roentgens). In fact, it turned out that the radiation ranged from 10 to 100 roentgens per hour.

Tourists, meanwhile, were sent for a medical examination. Doctors soon concluded that they were completely healthy. The press began a hunt for Mordhort and Mobley. They held a press conference at which they cheerfully talked about their adventures.

On the subject: What weapons will develop Russia and the United States after the collapse of the rocket treaty

Journalists even wanted to organize a flight to the wintering place, but in the end it did not take place. On 31 of January, four paratroopers were thrown into the camp, who remained there for some time to guard the place and feed the dogs left after the evacuation of tourists.

"Pig" in the cold

The group continued the search. They were complicated by a short daylight hours. It took about two hours to fly to the place of detection, then the search participants stood in the frost at 40 degrees, blown by a strong wind, while the chip was packed. Another two hours left to fly back. This was the whole working day.

One day, one of the teams, which flew out in search and landed far from the main camp, did not start a helicopter, and they had to spend the night in tents. The scientists had an unforgettable experience - especially those who flew in from hot Las Vegas, where the Nuclear Emergency Response Team (NEST, subordinate to the US Department of Energy) was located.

In the following days, several debris was discovered with relatively weak radiation at about 20 X-ray per hour.

Also, the search team came across an object with strong radiation near 200 X-ray per hour. Two hours next to such an object may be enough to receive severe radiation sickness or, in some cases, even a lethal dose.

Photo: Wikipedia /Natural resources canada

To transport this debris, experts made a lead container weighing half a ton, nicknamed “the pig.” The fragment was clamped with tongs and quickly thrown into the “pig”. The process was observed by Canadian Defense Minister Barney Dunson and three dozen journalists.

On February 10, multiple sources of mild radiation were detected on the ice of Great Slave Lake. Upon landing, the team found a large number of small particles ranging from microscopic to the size of a corn grain. Analysis in the laboratory showed that these were particles from the reactor core.

Scientists understood what happened to the reactor core - it apparently burned out in the atmosphere, but not completely, and the unburnt particles were blown away by the wind over an area of 80 thousand square kilometers. The area of infection was determined towards the end of February.

The leadership of the search operation was faced with a new task: how to clear such a vast area of microscopic radioactive particles? Moreover, the distance between them could be several hundred meters.

The territory was divided into sectors and began to be examined from helicopters that could fly low and catch small bursts of radiation with the help of equipment. People broke into groups and combed areas in which helicopters spotted an excess of background. The discovered particles, along with the snow, were simply loaded with shovels into plastic bags. Work continued for several weeks.

Of particular difficulty was the communication with the indigenous peoples of North America.

At the start of the operation, several hundred Inuit gathered in a school gym in the village of Baker Lake to explain why dozens of troops and equipment were disrupting their normal way of life. The Inuit's native language, Inuktitut, doesn't have words for "satellite" or "radiation," so the speakers had to get creative.

Inuit asked the military what radiation could do with deer, fish, and people. As a result, they accepted all the explanations and three days later in the same sports hall performed a traditional dance with drums for the search group.

Soviet "aid" to Canada

By the end of March, American specialists began to gradually fly home. At the peak of searches, about 120 scientists and military from the USA participated in them.

Operation Morning Light officially lasted 84 days. A total of 66 kilograms of debris were recovered. All of them were radioactive to varying degrees, except for one fragment weighing almost 18 kilograms.

During April, work continued in laboratories and offices. The Canadian authorities decided that the objectives of the search operation were fulfilled: the danger to the population and wildlife was minimized.

On the subject: Millions of people gathered to storm the secret base of the United States to save the aliens

Officials in the US and Canada were very afraid of the panic of the population. But the residents of Yellowknife and surrounding towns reacted calmly to events.

The only inconvenience for them was the influx of military, scientists and journalists. At the same time, hotel and cafe owners made good money. Sig Sigwaldason, editor-in-chief of the local Yellowknifer newspaper, joked that the Russians had given the local economy more in a few days than the Canadian government had for a year.

For the government, the economic effect was negative. The operation cost a lot of money. Canada billed the Soviet Union for 6,1 million dollars. In April 1981, the USSR agreed to pay half this amount.

The Americans and Canadians did not lose out, wrote academician Alexander Zheleznyakov: “All the collected fragments of the satellite fell into their hands. Although only the remains of the beryllium reflector and semiconductor batteries were of value. It was probably the most expensive radioactive waste in human history."

In the negotiations, the USSR insisted that Canada violated international standards by inviting the United States to participate in the operation and refusing Soviet engineers.

“We will not put anyone on trial”

Despite the absence of human casualties, the fall of the satellite turned into a serious scandal for the Soviet Union.

It should be noted that spacecraft with nuclear power sources have fallen before, including American ones. For example, as a result of the well-known accident at Apollo-13, an RTG with 3,9 kg of plutonium-238 fell into the ocean, which was used as a power source in the lunar module. The isotope will be radioactive for several thousand more years, but radiation does not seem to penetrate the environment due to the robust RTG housing.

But the crash of Cosmos 954 was the first crash of a working nuclear reactor on the territory of a sovereign state, and not in the ocean. Moreover, it is an ally of the United States, with whom the USSR was in a state of Cold War.

UN has several countries demanded, so that spacefaring nations take additional safety measures when launching nuclear-powered spacecraft. The USSR insisted that the crash of Cosmos 954 was not a serious incident.

“We will not put anyone on trial or remove anyone from work,” said the head of the Soviet nuclear industry, Efim Slavsky, at one of the meetings after the accident. recalled in his book, the scientist Arkady Kruglov.

On the subject: How to escape in the event of a nuclear war

The Soviet Union temporarily stopped launches of satellites with reactors. Security system finalized. A backup system was added to the main system, which, in the event of an emergency, took the satellite to the orbit of the burial site, which ejected fuel cells from the reactor vessel in the event of the spacecraft entering the Earth’s atmosphere. This ensured the combustion of hazardous substances and debris in the atmosphere.

In 1981, launches were resumed. In 1982, the Cosmos-1402 satellite was launched, which, like Cosmos-954, got out of control and fell in early 1983. In the American press right there remembered events of five years ago. This time the satellite fell into the ocean, and the reactor core burned out in the atmosphere.

Subsequently scientists Found outthat the fall of Cosmos-1402 led to the fallout of radioactive strontium-89 along with rain in Fayetteville, Arizona. In 1984, air samples were taken at an altitude of 27-36 km, which showedthat about 45 kilograms of uranium-235 from the Kosmos-1402 reactor were sprayed into the atmosphere.

Launches of spacecraft with nuclear reactors continued until the 1988 year. As Gudilin and Slabky wrote, the reasons for the termination of the program were the relatively low technical characteristics of such power plants and the requirements of the international community to stop using nuclear facilities in space.

Read also on ForumDaily:

Six radiation disasters in the USSR, about which you have never heard

Study: what will be the war between NATO and Russia

Child of Chernobyl: the story of an only child born and raised in the exclusion zone

Subscribe to ForumDaily on Google NewsDo you want more important and interesting news about life in the USA and immigration to America? — support us donate! Also subscribe to our page Facebook. Select the “Priority in display” option and read us first. Also, don't forget to subscribe to our РєР ° РЅР ° Р »РІ Telegram and Instagram- there is a lot of interesting things there. And join thousands of readers ForumDaily New York — there you will find a lot of interesting and positive information about life in the metropolis.