How cities live on the border of the United States and Mexico, where Trump wants to build a wall

While the record-breaking shutter lasts in the United States — a partial suspension of government work because of a conflict over the idea of building a border wall — journalists from the British newspaper The Guardian visited five places on the border of the United States and Mexico.

Photo: Depositphotojuan

In their report, they tell how these frontier cities live and whether Trump’s rhetoric insisting on allocating $ 5 billion to build a wall is in line with the local realities. New Time offers to get acquainted with the full translation of the material.

Trump Presidency Symbol

Donald Trump's "big, beautiful wall" has become the hallmark of his presidency. It was this promise, more than any other, that galvanized his supporters and angered his opponents, and Trump's stubborn adherence to this idea has now brought much of the US government into a historic shutdown.

The power of Trump's wall—for both his supporters and his critics—comes from its simplicity. Let's build it high, let's build it long—he promised 1000 miles—and America will be safe again.

However, how does this simple concept relate to the complexity of the border itself? Taken together, the 1 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border is an area of astonishing diversity—terrain, land use, urban-rural mix, ethnic composition. The border crosses desert, river, mountains and sea.

The political views of the 7,5 million people who live in the border regions of the United States also differ in diversity. Some of them are ardent supporters of Trump's wall. Others believe that their future—and the future of all of America—is inextricably linked to the future of their neighbor to the south.

Friendship over the fence

Walk for 45 minutes along salt marshes and sand dunes on a deserted beach - except for the occasional tourist on horseback - and you'll reach a steel fence that juts out into the Pacific Ocean.

This is exactly the place where Trump would like to start building his wall if he found the necessary billions of dollars. In view of the funding impasse that triggered the shatdaun, administration officials began to demonstrate what was already built here, as well as repair the two-mile section of the Calexico fence in 100 miles east, like Trump's wall. However, this is not her.

The length of the wall built by Trump since he came to the White House in January 2017, is zero.

It is the westernmost point of the US-Mexico border on the outskirts of San Ysidro, California, a suburb of San Diego that is home to one of the busiest border crossings in the world. This is where the hopes of thousands of migrants trying to reach the United States each year are often dashed.

The fence extends just where the waves break, and reaches 15 or 20 feet in height, and not at all those formidable 30 feet that the president requires.

Next to this section of the fence is the Friendship Park, a section of interethnic territory, where it is allowed to meet people close on both sides of the border. This is a very paradoxical name, given the hostility that Trump spawned with his obsession with a wall.

Фото: Depositphotos

Outside Friendship Park - which can only accommodate 10 visitors at a time - separated families and friends have to make do with waving to each other from a distance. Today the American side is deserted except for a lone American man and a father and little boy on the Mexican side looking north. “USA!” says the man, pointing his son through a gap in the fence to the promised land.

From San Isidro, the fence extends along the 46 of the following 60 miles of the border, before finally giving way to the inexorable wilderness. This is 46 from 654 miles of existing fence, much of which has fallen into disrepair, albeit in varying degrees.

These hundreds of miles of double-reinforced fencing and chain-link fencing are the product of a different political era, when some degree of bipartisan consensus [of Democrats and Republicans in Congress] was still possible. The fence was largely funded by a 2006 immigration compromise reached under former President George W. Bush (the Secure Fence Act).

Compromise seems unthinkable these days. Trump has laid out a strictly bipolar vision of the border: on his side of the territorial demarcation are the rule of law, industriousness and freedom; on the other side there is crime, gangs and drug smuggling.

The purpose of this wall, according to Trump's dystopia, is to prevent America from being taken over by dark forces that have prevailed over its neighbor. In his recent address to the nation from the Oval Office, he said: “Thousands of Americans have been brutally murdered over the years by those who entered our country illegally, and thousands more will die if we do not act now.”

But talk to people in San Ysidro - on the US side of the border - and they will tell you how the US government instills fear and intimidates them.

In this city, where 90% of residents speak at home in Spanish, the land south of the border means not lawlessness and evil, but family, friends and affordable health care. If there is a dystopia, then these are not the Mexicans that Trump describes them, but toughened militarism, which is rapidly spreading by the United States, teeming with helicopters, barricades and armed border patrols.

“The last few months have felt like you're in a war zone, it's so dramatic,” said Lisa Cuestas, head of Casa Familiar, a nonprofit social services organization in San Isidro.

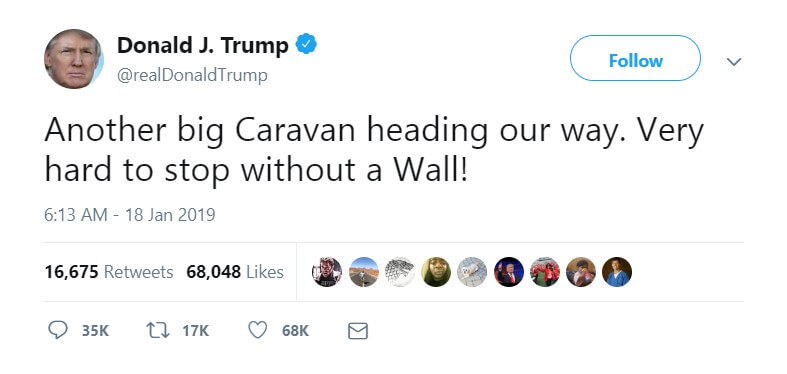

The militarization has accelerated since the arrival in Tijuana, the city on the Mexican side, of a caravan of Central American migrants that Trump touted as an “immigration invasion” during the midterm elections in November. Now the caravan members are stranded in Mexico, and the barbed wire has spread everywhere like a mutant weed.

Estrella Flores has a family and work in San Isidro, she works with young people at Casa Familiar, but lives in Tijuana with her husband and 18-month-old baby. Her trips to work turned into hell due to the harsh cross-border measures of the Trump administration.

“When I first crossed the border, reinforced with barricades, barbed wire and helicopters, I thought: “Am I really in a war zone? What's happening? I'm just trying to get to work." This is no longer a friendly border, and the situation could turn out very badly, very soon.”

This opinion is common throughout California. A survey conducted by the San-Diego Union-Tribune after Trump's speech from the Oval Office showed that 56% of Californians oppose the idea of the wall, while it is supported by 34% of respondents.

This is not surprising in a state that is a stronghold of progressive politics in the United States. But California is also important because it has more undocumented migrants than any other state—2,4 million versus 1,7 million in Texas, for example.

Not far from here is the site where eight different pieces of Trump's wall prototypes were erected. He came here in March 2017 to pose for photographs in front of giant slabs of concrete and steel. Now they languish idle and rust.

According to a recent report by the United States Audit Office, eight sample sections were rife with design and construction flaws. The US Border Guard checked the plates and found that they could be cracked.

Death in the desert

The first morning rays of light glisten on the frozen thorns of cholla cacti when 30 volunteers in neon yellow shirts split apart to comb the desert under a pale pink sky. Eli Ortiz, leader of Águilas del desierto (Desert Eagles), assembles his team, which was getting all night from San Diego to Adjo, Arizona. He tells them that the last time they searched the area, they found the remains of a 11 man.

Search dogs join the volunteers to assist in these dark searches. The dog named Zabra, whose last task was to detect victims of California forest fires, was not used to the desert terrain. He has to stop every few hundred yards so that the thorns are pulled out of his paws.

Unexploded ordnance dropped by the US military at the exercise remains one of the serious threats to migrants. Here Trump could well count on the metaphorical wall. This is the most popular, but also the most deadly corridor for migrants across the Sonoran desert.

There is not enough water here, and the temperature in the summer months rises above 120F (49C). According to official data from the US Border Service, over the past 20 years, 7 thousand 209 deaths have been recorded along the south-western border, but this is probably far from complete statistics.

Despite the human tragedy, federal prosecutors saw fit to prosecute nine volunteers from the humanitarian group No More Deaths. Their offenses were “littering” and driving on restricted roads in the Cabeza Prieta Nature Reserve. All nine will appear in federal district court in Tucson.

“The irony is that we are not allowed to drive here or leave water here because it is a protected conservation area. But at the same time, border patrol agents drive their trucks and ATVs far off the road, fly helicopters and fly drones wherever they want,” one of the nine defendants, Parker Deighan, tells The Guardian.

Trump's policy of "prevention through deterrence" is forcing migrants to take more risks. As legal entry into the U.S. through official crossings becomes increasingly restricted, migrants are being “transported” away from fenced areas of the border and toward the desert.

One of the few cities in the area is Aho. Today it is a ghost town, as the copper mine here was closed in the 1980's. Since then, most residents have settled down to the main local employer: the border guard.

Samaritans from Aho recently gathered in the square to remember the people who died in the surrounding wilderness. They laid out 118 white crosses, one for each of those killed in 2018. Those whose bones had not yet been identified were referred to as desconocido - "unknown".

Фото: Depositphotos

Get into the USA

Before Trump decided to throw a handout to his voters during the mid-term elections in 2018, sending more than 5 to thousands of active soldiers at the border, the gate at the checkpoint in Lukville, Arizona, was almost always open. American tourists, trying to get away from winter, poured in this careless river across this stretch of border to the beach at Rocky Point on the Mexican coast, an hour's drive from here to the south.

Trump's tightening of border policies has limited more than just beachgoers, who now pass through half-closed gates. Over the past two months, the US military has brought with it a barbed wire concertina and shipping containers designed to block entry and create an impenetrable barricade in case another caravan - or "immigrant invasion" - arrives.

Not that there are any signs of such a thing... Most of the traffic through Lukeville is commercial and passenger, and the main target for federal agents is not migrants, but drugs.

This is another of the myths propagated by the Trump administration - that America is overrun with drugs that entered the country due to the lack of a wall. In a speech from the Oval Office last week, Trump said the "border wall will pay for itself very quickly" by stopping the flow of illegal drugs - implying that drugs entered the US through open sections of the border.

But it is not. In fact, most of the illegal drugs are hidden in cars and trailers passing through international bridges and small border points, such as Luquille. The annual report on the drug trafficking situation published by the Anti-Drug Administration in 2018 indicated that up to 90% of such drugs as heroin enter the country through official border points.

Another controversy is that Trump insists that legal immigrants report to border crossing points. However, for those who do this, he extremely complicated the procedure for obtaining refugee status. In November, the Trump administration announced that asylum would be denied to anyone who tried to cross the border illegally, although since then the federal court has temporarily blocked new measures.

Meanwhile, a new "accounting" system was introduced, which slowed down the work of authorities at legal points of entry.

The result has left a growing number of desperate families, most from the trio of violence-plagued Central American countries - Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala - stranded in Mexico.

In Lukville, asylum-seekers who followed Trump's orders and legally arrived at the border checkpoint were simply sent back. The Guardian spoke to Alberto (name changed) in a refugee camp on the Mexican side. In November, he came to Lukville and sought asylum.

A border guard told him to get out, saying that he had arrived at an inopportune time. Alberto was left on the street, where a few days before, members of the mafia threatened to kill him if they saw him again.

Volunteer groups working with immigrants protested, and US Customs and Border Protection apologized. Now, when asked whether they accept asylum seekers, the service in Lukeville repeats the official mantra: “Asylum seekers are accepted at all crossing points.”

This does not mean that such applications will be successful. Alberto for the second time tried to reach the US authorities. In two weeks time, he will testify before an immigration judge.

Фото: Depositphotos

Twin Cities

There is no place along the border that subverts Trump's dystopian vision more powerfully than El Paso. The Texas city is so intertwined with the Mexican city of Ciudad Juarez - just south across the Rio Grande River - that the two are virtually inseparable.

Almost 3 million people live in two cities - about the same as in Chicago. About 20 pedestrians and more than 35 vehicles arrive in El Paso from Mexico every day—many to work, others to school or shopping.

This is a two-way flow: Americans from El Paso also regularly move to Juárez to visit their family or relax in nightclubs.

80% of El Paso residents are of Latin American origin, and a quarter of the city’s population was born outside the United States.

Mary Gonzalez, a Democratic representative in the Texas House of Representatives from El Paso, says, “This is a very welcoming, diverse, diverse, welcoming and loving community. This human component is not taken into account when discussing the border.”

Retail sales on the American side of the twin cities, according to general estimates, bring up to $ 10 billion per year, with a fifth of it being Mexican buyers.

Contrary to this reality, Trump paints a picture of rampant crime and the threat of violence imported into the United States. This is a particularly strong argument for El Paso, given the historically high homicide rate in neighboring Juarez.

Last year, the figure rose again to nearly 200 killed per month. However, crime in El Paso on the US side of the border remains relatively low. The number of violent crimes has dropped sharply, from 6,5 in 1993 to 3 today.

That's why Beto O'Rourke, a rising star in the Democratic Party and the city's former congressional representative, called El Paso "the safest city in America" as part of his campaign for Senate in November. (His statement was not entirely accurate—fact checkers found it to be only “half true.”)

O'Rourke failed in his desire to overthrow [the incumbent Republican Sen.] Ted Cruz in the midterm elections. However, the fact that he lacked only 3% to win, suggests that Texans can be much more open to liberal positions on immigration than often assumed, and it’s not so noticeable to keep up with Trump.

Opinion polls show that, although most Texans are worried about the illegal entry of immigrants into the country, most of them are against Trump's wall.

Some even suggest that El Paso could be a harbinger for the rest of America. As Josiah Heyman, director of the Center for Inter-American and Border Studies, said, “El Paso is a place where there is a vision of the future, where people, instead of being part of an insular, defensive community, can find the joy of connection with others.”

At the turn: Rio Grande river

Travel 40 miles east of El Paso, along the Rio Grande to Tornillo, and you’ll feel half the world from big cities. Vast open spaces full of orchards, dairy farms and nut plantations.

However, car patrols of the US Border Guard are closely watching everything around.

Of the 1 thousand 317 miles of the border, not equipped with fences or other barriers, most of it runs along the Rio Grande river with a length of 1 thousand 248 miles. It serves as a demarcation line between the two countries all the way from El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico.

The powerful currents, towering canyons and cliffs that rise to 50 feet in the Big Bend Park area reduce the need to erect a fortified barrier throughout most of the river bed.

However, Trump does not overlook the Rio Grande in his draft wall. Of the $ 5,7 billion it requires from Congress, the lion’s share should go to building a section of a wall along the river that is more than 100 miles away.

Here, just outside Tornillo, the existing fence, which extends westward to Sunland Park in New Mexico, has a gap of 10 miles. Despite the absence of an artificial barrier, most of the locals go about their business without fuss and panic.

Miguel Alvarez, who has lived near the border for the past 25 years, said the fence has made little difference. “You can still see small groups of people passing [across the border], as they did before all the crossings,” says the man.

The farmer, who did not want to give his name, admitted that he would feel safer if the hole in the fence was closed. “I haven’t had any problems with people crossing the border, but you never know,” he notes.

Tornillo himself was at the center of national attention after the Trump administration chose the Marcelino Serna frontier post south of the city in order to place thousands of migrant children in the tent camp, not accompanied by adults. The camp was thought to be temporary and was intended for hundreds of children separated from their families as a result of Trump's attempt to suppress the flow of migrants.

However, it quickly grew to 2,4 thousand places, becoming a symbol of Trump’s harsh policy of separating migrant families as a deterrent factor for them.

In November, one of the supervisory authorities warned authorities that conditions in the tent camp put the lives of children at risk, and since then their numbers have decreased until the last teenager was taken out of this place in January 2019. As far as local residents know, the camp itself cannot be quickly turned down.

Local eager for everything to return to normal. Or, at least, returned to what would be considered normal in our day.

Read also on ForumDaily:

What and how does Trump want to build on the border with Mexico?

NBC: Trump's steel wall sample tests fail

How much it costs every illegal for taxpayers: updated data

What the world media writes about Trump's war on Congress and its appeal to the nation

Trump's urgent appeal to the nation: US 'humanitarian crisis' can be resolved in 45 minutes

What is the condition of the wall on the border between the USA and Mexico?

Subscribe to ForumDaily on Google NewsDo you want more important and interesting news about life in the USA and immigration to America? — support us donate! Also subscribe to our page Facebook. Select the “Priority in display” option and read us first. Also, don't forget to subscribe to our РєР ° РЅР ° Р »РІ Telegram and Instagram- there is a lot of interesting things there. And join thousands of readers ForumDaily New York — there you will find a lot of interesting and positive information about life in the metropolis.